In the lead-up to Game Informer’s return back in March, I wanted to replay two of my favorite short, instant-action experiences. I hadn’t played Super Mario 64 or Portal all the way through since their original releases on Nintendo 64 and Xbox 360/PC, respectively, and they both rank highly on my favorite games of all time, so I was excited to return to these formative experiences. While they are foundational video games for entirely different reasons, one common thread tied them together in my mind when I played them back to back: their mastery of tutorialization.

In most cases, a video game tutorial is similar to learning how to conjugate verbs in a foreign language. Yeah, it’s no fun, but it’s essential to building a foundation that will give you the tools you need to thrive moving forward. In many games, tutorials are doled out gradually in either a dedicated section before the proper game starts or through early missions full of pop-ups. It feels like prepping you for a long journey ahead, which is apt, given that is exactly what most games have become at this point.

When the Nintendo 64 launched in 1996, the Super Mario 64 development team had the unenviable task of not only teaching players how to play their new game, but also the 3D platforming genre as a whole. Toads are scattered throughout Peach’s Castle, Lakitu gives you a crash course on controlling the camera, and there are sometimes pop-ups explaining new mechanics, but they are few and far between. The main tutorial happens outside the castle, where Mario emerges from a pipe and is immediately given a rudimentary playground with no enemies or hazards. It’s here that first-time players likely discover Mario’s ability to triple-jump, climb trees, and even swim. Having the first unspoken mission of Super Mario 64 as “enter the castle” also requires players to familiarize themselves with joystick controls in a 3D space – likely for the first time if they were playing it in 1996.

The Portal developers had less foundational tutorialization to lay, but their challenge instead was in the fact that gamers already knew how physics-based puzzles and first-person shooter gameplay worked. So when the team at Valve introduced a completely new mechanic that changes every aspect of the experience, they had to essentially break players out of habits they had developed from years of playing games like Halo, Quake, and even Valve’s own Half-Life. Valve seemingly knew this, which is why they coined the term “thinking with Portals” to describe the sensation of when you finally start breaking your brain out of established habits and start learning new skills and ways of thinking that become second nature for the rest of your time playing it.

It’s a similar sensation to what I experienced playing The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom in 2023. I’ve played through Breath of the Wild in its entirety twice, so when Tears of the Kingdom introduced transformative elements to incredibly familiar gameplay, it took me tens of hours to remember that I could phase through ceilings, fuse weapons, or even build tools and vehicles. Tears of the Kingdom does a fine job of on-ramping you to these new mechanics, but it doesn’t feel like it rewires your brain the way the opening puzzles of Portal do.

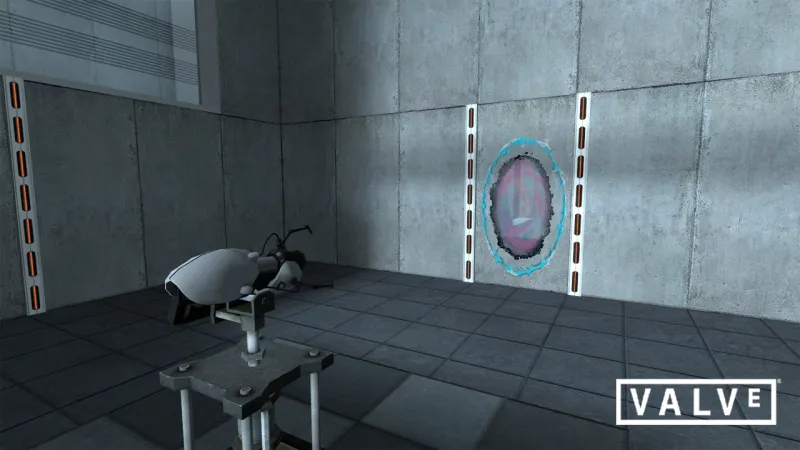

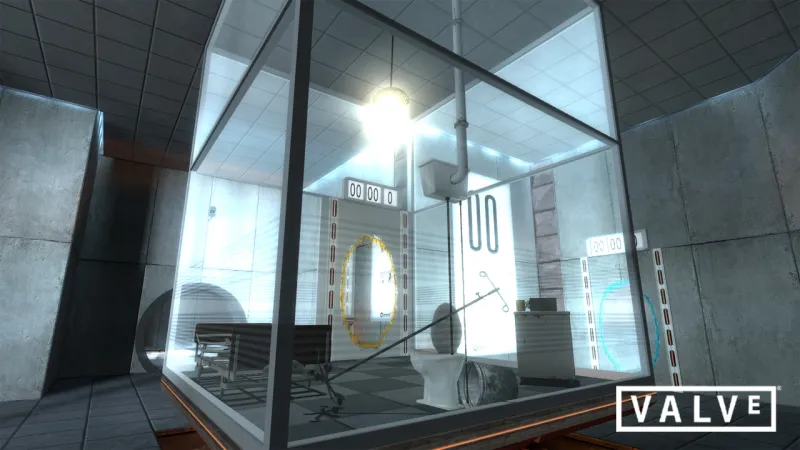

Portal tosses seemingly insurmountable puzzles at you right off the bat, but even before that, when you fire your first Portal to exit Chell’s stasis room, the act of simply seeing Chell from a different angle through the Portal was enough to understand how portals work. Yes, GLaDOS peppers in hints and nudges amidst her bullying, but it’s balanced against the feeling of throwing players into the deep end until they are forced to swim, or in this case, rewire their brains to think with portals. After the initial moments of the game telling you how to fire your portals, the slow introduction of mechanics never feel overly turotialized or hand-holdy. Instead, they simply feel like the next evolution, the next step up, as more mechanics overlap en route to the final approach to your confrontation with GLaDOS. It’s a short and sweet experience, but one that is appropriately paced and with mind-melting mechanics that feel perfectly taught.

Perhaps the most stark difference comes when you juxtapose these approaches to tutorialization against bigger, more complicated modern experiences. I don’t have the answers for how a studio should teach me how to play a game like Assassin’s Creed Shadows, but what I do know is that every time I turn that game on, I have to read through the controls screen again or die multiple times before I remember how to perform even basic tasks. The hours I’ve spent playing through the in-game lessons disguised as missions in Shadows – not to mention the hundreds of hours I’ve poured into the series as a whole – arrive in a way that my brain just doesn’t retain them. Maybe it’s the fact that many are delivered via a text pop-up, or maybe it’s because there are so many distinct actions at your fingertips at any given moment. In contrast, Mario and Portal are relatively simple in the number of actions you can perform. Still, I can’t help but feel there has to be a better way for modern games to supply these instructions in ways that are not only memorable but also fun.

Super Mario 64 and Portal blazed enough trails that there are any number of reasons game designers should study them. But when playing tutorials in most modern games feels like the eating-your-leafy-greens portion of the overall experience, it tells me that more lessons are still to be harvested from these seminal games. That’s not to say that no modern games have good tutorials – look no further than two of the best games of 2024, Balatro and Astro Bot, as examples of good introductions. But those stick out as strong examples for less complex games. Most games today are far more complicated than in 1996 or even 2007, and as a result, require more in-depth tutorials. But if Portal, Super Mario 64, Balatro, and Astro Bot are any indication, simplicity, streamlining, and learning from doing instead of hearing or reading can help players absorb the information and stay engaged through what can sometimes be the most boring part of a game.